May 1, 2019 - Congressional Budget Office

This report describes the primary features of single-payer systems, and it discusses some of the design considerations and choices that policymakers will face in developing proposals for establishing such a system in the United States.

View Document

592.6 KB

Congressional interest in substantially increasing the number of people who have health insurance has grown in recent years. Some Members of Congress have proposed establishing a single-payer health care system to achieve universal health insurance coverage. In this report, CBO describes the primary features of single-payer systems, as well as some of the key considerations for designing such a system in the United States.

Establishing a single-payer system would be a major undertaking that would involve substantial changes in the sources and extent of coverage, provider payment rates, and financing methods of health care in the United States. This report does not address all of the issues that the complex task of designing, implementing, and transitioning to a single-payer system would entail, nor does it analyze the budgetary effects of any specific bill or proposal.

About 29 million people under age 65 were uninsured in an average month in 2018, according to estimates by CBO and the staff of the Joint Committee on Taxation. Although a single-payer system could substantially reduce the number of people who lack insurance, the change in the number of people who are uninsured would depend on the systemfs design. For example, some people (such as noncitizens who are not lawfully present in the United States) might not be eligible for coverage under a single-payer system and thus might be uninsured. This report uses the term guniversal coverageh to characterize systems in which virtually all people in an eligible population have health insurance.

Although single-payer systems can have a variety of different features and have been defined in many ways, health care systems are typically considered single-payer systems if they have these four key features:

In the United States, the traditional Medicare program is considered an example of an existing single-payer system for elderly and disabled people, but analysts disagree about whether the entire Medicare program is a single-payer system because private insurers play a significant role in delivering Medicare benefits outside the traditional Medicare program. Medicare beneficiaries can choose to receive benefits under Part A (Hospital Insurance) and Part B (Medical Insurance) in the traditional Medicare program or through one of the private insurers participating in the Medicare Advantage program. Those private insurers compete for enrollees with each other and with the traditional Medicare program, and they accept both the responsibility and the financial risk of providing Medicare benefits. The Medicare prescription drug program (Part D) is delivered exclusively by private insurers.

Australia, Canada, Denmark, England, Sweden, and Taiwan are among the countries that are typically considered to have single-payer systems. Although some design features vary across those systems, they all achieve universal coverage by providing eligible people access to a specified set of health services regardless of their health status (see Table 1). Other countries, including Germany, the Netherlands, and Switzerland, have achieved universal coverage through highly regulated multipayer systems, in which more than one insurer provides health insurance coverage.

Establishing a single-payer system in the United States would involve significant changes for all participants— individuals, providers, insurers, employers, and manufacturers of drugs and medical devices—because a single-payer system would differ from the current system in many ways, including sources and extent of coverage, provider payment rates, and methods of financing. Because health care spending in the United States currently accounts for about one-sixth of the nationfs gross domestic product, those changes could significantly affect the overall U.S. economy.

For both the economy and participants in the singlepayer system, the consequences would depend on how all stakeholders responded to the systemfs various design features and how those responses interacted within the health care system and with the rest of the economy. The magnitude of those responses is difficult to predict because the existing evidence is based on previous changes that were much smaller in scale. Although policymakers could design a single-payer system with an intended objective in mind, the way the system was implemented could cause substantial uncertainty for all participants. That uncertainty could arise from political and budgetary processes, for example, or from the responses of other participants in the system. To mitigate uncertainty during the systemfs implementation, policymakers could develop administrative and governance structures to continuously monitor its performance and respond quickly to any issues that arise.

The transition toward a single-payer system could be complicated, challenging, and potentially disruptive. To smooth that transition, features of the single-payer system that would cause the largest changes from the current system could be phased in gradually to minimize their impact. Policymakers would need to consider how quickly people with private insurance would switch their coverage to the new public plan, what would happen to workers in the health insurance industry if private insurance was banned entirely or its role was limited, and how quickly provider payment rates under the single-payer system would be phased in from current levels. Although the transition toward a single-payer system would require considerable attention from policymakers, this report does not focus on the transition process.

Coverage. In a single-payer system that achieved universal coverage, everyone eligible would receive health insurance coverage with a specified set of benefits regardless of their health status. Under the current system, CBO estimates, an average of 29 million people per month—11 percent of U.S. residents under age 65—were uninsured in 2018. Most (or perhaps all) of those people would be covered by the public plan under a single-payer system, depending on who was eligible. A key design choice is whether noncitizens who are not lawfully present would be eligible. An average of 11 million people per month fell into that category in 2018, according to CBOfs estimates, and they might not have health insurance under a single-payer system if they were not eligible for the public plan. About half of those 11 million people had health insurance in 2018.

People who are currently insured receive their coverage through various sources. Almost all people age 65 or older, or about one-sixth of the population, receive coverage through the Medicare program. CBO and the Joint Committee on Taxation estimate that, in 2018, a monthly average of about 243 million people under age 65 had health insurance. About two-thirds of them, or an estimated 160 million people, had health insurance through an employer. Roughly another quarter of that population, or about 69 million people, are estimated to have been enrolled in Medicaid or the Childrenfs Health Insurance Program (CHIP). A smaller proportion of people under age 65 had nongroup coverage, Medicare, or coverage through other sources.

Under a single-payer system, people who currently have private insurance would enroll in the public plan. Depending on the design of the single-payer system, however, those people might be allowed to retain private coverage that supplements the coverage under the public plan. People who currently have public coverage could continue to have such coverage under a single-payer system, although their covered benefits and cost sharing might change, depending on the systemfs design.

Costs. Government spending on health care would increase substantially under a single-payer system because the government (federal or state) would pay a large share of all national health care costs directly. Currently, national health care spending—which totaled $3.5 trillion in 2017—is financed through a mix of public and private sources, with private sources such as businesses and households contributing just under half that amount and public sources contributing the rest (in direct spending as well as through forgone revenues from tax subsidies). Shifting such a large amount of expenditures from private to public sources would significantly increase government spending and require substantial additional government resources. The amount of those additional resources would depend on the systemfs design and on the choice of whether or not to increase budget deficits. Total national health care spending under a single-payer system might be higher or lower than under the current system depending on the key features of the new system, such as the services covered, the provider payment rates, and patient cost-sharing requirements.

Other Consequences. A single-payer system would present both opportunities and risks for the health care system. It would probably have lower administrative costs than the current system—following the example of Medicare and of single-payer systems in other countries—because it would consolidate administrative tasks and eliminate insurersf profits. Moreover, unlike private insurers, which can experience substantial enrollee turnover over time, a single-payer system without that turnover would have a greater incentive to invest in measures to improve peoplefs health and in preventive measures that have been shown to reduce costs. Whether the single-payer plan would act on that incentive is unknown.

An expansion of insurance coverage under a single-payer system would increase the demand for care and put pressure on the available supply of care. People who are currently uninsured would receive coverage, and some people who are currently insured could receive additional benefits under the single-payer system, depending on its design. Whether the supply of providers would be adequate to meet the greater demand would depend on various components of the system, such as provider payment rates. If the number of providers was not sufficient to meet demand, patients might face increased wait times and reduced access to care. In the longer run, the government could implement policies to increase the supply of providers.

Because the public plan would provide a specified set of health care services to everyone eligible, participants would not have a choice of insurer or health benefits. Compared with the options available under the current system, the benefits provided by the public plan might not address the needs of some people. For example, under the current system, young and healthy people might prefer not to purchase any coverage, or they might prefer to purchase coverage with high deductibles or fewer benefits. And, unlike a system with competing private insurers, the public plan might not be as quick to meet patientsf needs, such as covering new treatments. Policymakers could try to design the governance structure of the single-payer system so that it would respond to the shifting needs of enrollees in a timely manner.

In addition to its potential effects on the health care sector, a single-payer system would affect other sectors of the economy that are beyond the scope of this report. For example, labor supply and employeesf compensation could change because health insurance is an important part of employeesf compensation under the current system.

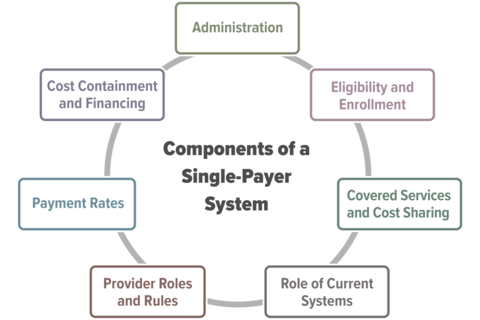

This report focuses on the following key design components and considerations for policymakers interested in establishing a single-payer system: